About us

Learn how GA4GH helps expand responsible genomic data use to benefit human health.

Learn how GA4GH helps expand responsible genomic data use to benefit human health.

Our Strategic Road Map defines strategies, standards, and policy frameworks to support responsible global use of genomic and related health data.

Discover how a meeting of 50 leaders in genomics and medicine led to an alliance uniting more than 5,000 individuals and organisations to benefit human health.

GA4GH Inc. is a not-for-profit organisation that supports the global GA4GH community.

The GA4GH Council, consisting of the Executive Committee, Strategic Leadership Committee, and Product Steering Committee, guides our collaborative, globe-spanning alliance.

The Funders Forum brings together organisations that offer both financial support and strategic guidance.

The EDI Advisory Group responds to issues raised in the GA4GH community, finding equitable, inclusive ways to build products that benefit diverse groups.

Distributed across a number of Host Institutions, our staff team supports the mission and operations of GA4GH.

Curious who we are? Meet the people and organisations across six continents who make up GA4GH.

More than 500 organisations connected to genomics — in healthcare, research, patient advocacy, industry, and beyond — have signed onto the mission and vision of GA4GH as Organisational Members.

These core Organisational Members are genomic data initiatives that have committed resources to guide GA4GH work and pilot our products.

This subset of Organisational Members whose networks or infrastructure align with GA4GH priorities has made a long-term commitment to engaging with our community.

Local and national organisations assign experts to spend at least 30% of their time building GA4GH products.

Anyone working in genomics and related fields is invited to participate in our inclusive community by creating and using new products.

Wondering what GA4GH does? Learn how we find and overcome challenges to expanding responsible genomic data use for the benefit of human health.

Study Groups define needs. Participants survey the landscape of the genomics and health community and determine whether GA4GH can help.

Work Streams create products. Community members join together to develop technical standards, policy frameworks, and policy tools that overcome hurdles to international genomic data use.

GIF solves problems. Organisations in the forum pilot GA4GH products in real-world situations. Along the way, they troubleshoot products, suggest updates, and flag additional needs.

GIF Projects are community-led initiatives that put GA4GH products into practice in real-world scenarios.

The GIF AMA programme produces events and resources to address implementation questions and challenges.

NIF finds challenges and opportunities in genomics at a global scale. National programmes meet to share best practices, avoid incompatabilities, and help translate genomics into benefits for human health.

Communities of Interest find challenges and opportunities in areas such as rare disease, cancer, and infectious disease. Participants pinpoint real-world problems that would benefit from broad data use.

The Technical Alignment Subcommittee (TASC) supports harmonisation, interoperability, and technical alignment across GA4GH products.

Find out what’s happening with up to the minute meeting schedules for the GA4GH community.

See all our products — always free and open-source. Do you work on cloud genomics, data discovery, user access, data security or regulatory policy and ethics? Need to represent genomic, phenotypic, or clinical data? We’ve got a solution for you.

All GA4GH standards, frameworks, and tools follow the Product Development and Approval Process before being officially adopted.

Learn how other organisations have implemented GA4GH products to solve real-world problems.

Help us transform the future of genomic data use! See how GA4GH can benefit you — whether you’re using our products, writing our standards, subscribing to a newsletter, or more.

Join our community! Explore opportunities to participate in or lead GA4GH activities.

Help create new global standards and frameworks for responsible genomic data use.

Align your organisation with the GA4GH mission and vision.

Want to advance both your career and responsible genomic data sharing at the same time? See our open leadership opportunities.

Join our international team and help us advance genomic data use for the benefit of human health.

Discover current opportunities to engage with GA4GH. Share feedback on our products, apply for volunteer leadership roles, and contribute your expertise to shape the future of genomic data sharing.

Solve real problems by aligning your organisation with the world’s genomics standards. We offer software dvelopers both customisable and out-of-the-box solutions to help you get started.

Learn more about upcoming GA4GH events. See reports and recordings from our past events.

Speak directly to the global genomics and health community while supporting GA4GH strategy.

Be the first to hear about the latest GA4GH products, upcoming meetings, new initiatives, and more.

Questions? We would love to hear from you.

Read news, stories, and insights from the forefront of genomic and clinical data use.

Attend an upcoming GA4GH event, or view meeting reports from past events.

See new projects, updates, and calls for support from the Work Streams.

Read academic papers coauthored by GA4GH contributors.

Listen to our podcast OmicsXchange, featuring discussions from leaders in the world of genomics, health, and data sharing.

Check out our videos, then subscribe to our YouTube channel for more content.

View the latest GA4GH updates, Genomics and Health News, Implementation Notes, GDPR Briefs, and more.

Discover all things GA4GH: explore our news, events, videos, podcasts, announcements, publications, and newsletters.

14 Feb 2022

The latest GDPR Brief, written by Mikel Recuero Linares, addresses recent developments by the EDPB and implications for genomic and health data sharing.

The latest GDPR Brief, written by Mikel Recuero Linares, addresses recent developments by the EDPB and implications for genomic and health data sharing.

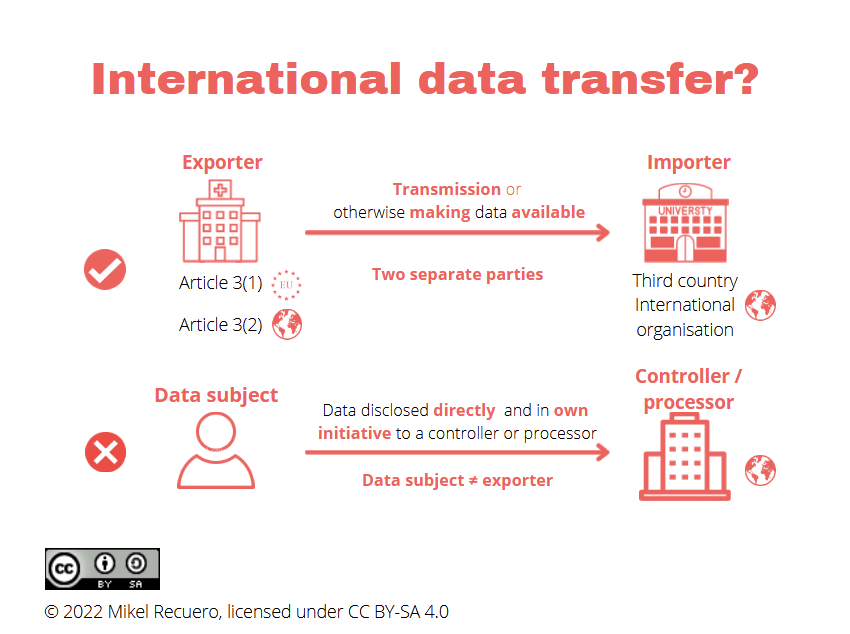

Seasoned readers of the GA4GH GDPR Brief will note that the GA4GH GDPR and International Health Data Sharing Forum have addressed the topic of international data transfers on numerous occasions. However, the concept of ‘international data transfer’ has not yet been examined. The reason for this is that neither the GDPR, nor case law, nor European authorities have so far provided a robust definition of this term.

As an attempt to shed some light on this issue, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) adopted its ‘Guidelines 05/2021 on the interplay between the application of Article 3 and the provisions on international transfers as per Chapter V of the GDPR’ and opened a public consultation period, which ended on January 31st, 2022.

What constitutes an ‘international data transfer’?

According to the EDPB, an international data transfer will exist when the following three criteria are cumulatively met:

What are the implications for genomic and health data sharing?

Firstly, although an organisation from a third country may already be subject to the GDPR, one or more transfer tools will nonetheless be required in order to export the data to this controller or processor.

For example, consider the case of a US-based organisation importing clinical personal data from a Spanish hospital to develop and test a health data management software to be commercialised in the EU. The US entity would already be subject to the GDPR by offering its services and products to data subjects in the Union but, in addition, it would have to rely on a data transfer mechanism. Certainly, at this stage, they may not rely on the Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) adopted by the Commission as this is expressly precluded by Recital 7 thereof in those cases where the importer is already subject to the GDPR based on Article 3.

Secondly, since ‘transfer’ is defined as the ‘disclosure of data by transmission or otherwise making it available’, the scenarios in which the rules on international transfers would apply, even if the data remains in the EU, are significantly extended. The expression ‘otherwise making data available’ is not further described but only alluded to, and a reference is made to previous EDPB Guidelines. This is critical for genomic and health data sharing, e.g. for burgeoning federated infrastructures, platforms or databases.

Consider a European federated platform that allows Canadian researchers to search and discover European data sets stored on European servers. Although the data may never ‘leave’ the EU, would the fact that these data can be displayed or remotely processed (even inside the EU) by the Canadian researchers fall within the concept of ‘otherwise making it available’? The EDPB fails to clarify this extent, and, if anything, such an omission would entail the risk of equating or confusing the terms of ‘processing’ and ‘transfer’. Therefore, it does not seem to be the intention of the European legislator to restrict any data processing operation carried out by controllers or processors in a third country, but only those that may undermine the level of protection of natural persons guaranteed both by the GDPR and Union law.

Lastly, as mentioned, direct disclosure of data at the initiative of the data subject does not constitute an international transfer, e.g. directly entering data in an online form. The GDPR may still apply but without the transfer tools being necessary. Hence, data and rights could be treated differently depending on who is transferring such data outside the EU boundaries. If the data are transferred directly by the data subject, this may result in a different degree of protection and of rights enforcement, since the implementation of Chapter V tools and other safeguards will no longer be required.

Further reading

Relevant GDPR provisions

Mikel Recuero is legal counsel and researcher at the Chair in Law and the Human Genome of the University of the Basque Country.

See all previous briefs.

Please note that GDPR Briefs neither constitute nor should be relied upon as legal advice. Briefs represent a consensus position among Forum Members regarding the current understanding of the GDPR and its implications for genomic and health-related research. As such, they are no substitute for legal advice from a licensed practitioner in your jurisdiction.