About us

Learn how GA4GH helps expand responsible genomic data use to benefit human health.

Learn how GA4GH helps expand responsible genomic data use to benefit human health.

Our Strategic Road Map defines strategies, standards, and policy frameworks to support responsible global use of genomic and related health data.

Discover how a meeting of 50 leaders in genomics and medicine led to an alliance uniting more than 5,000 individuals and organisations to benefit human health.

GA4GH Inc. is a not-for-profit organisation that supports the global GA4GH community.

The GA4GH Council, consisting of the Executive Committee, Strategic Leadership Committee, and Product Steering Committee, guides our collaborative, globe-spanning alliance.

The Funders Forum brings together organisations that offer both financial support and strategic guidance.

The EDI Advisory Group responds to issues raised in the GA4GH community, finding equitable, inclusive ways to build products that benefit diverse groups.

Distributed across a number of Host Institutions, our staff team supports the mission and operations of GA4GH.

Curious who we are? Meet the people and organisations across six continents who make up GA4GH.

More than 500 organisations connected to genomics — in healthcare, research, patient advocacy, industry, and beyond — have signed onto the mission and vision of GA4GH as Organisational Members.

These core Organisational Members are genomic data initiatives that have committed resources to guide GA4GH work and pilot our products.

This subset of Organisational Members whose networks or infrastructure align with GA4GH priorities has made a long-term commitment to engaging with our community.

Local and national organisations assign experts to spend at least 30% of their time building GA4GH products.

Anyone working in genomics and related fields is invited to participate in our inclusive community by creating and using new products.

Wondering what GA4GH does? Learn how we find and overcome challenges to expanding responsible genomic data use for the benefit of human health.

Study Groups define needs. Participants survey the landscape of the genomics and health community and determine whether GA4GH can help.

Work Streams create products. Community members join together to develop technical standards, policy frameworks, and policy tools that overcome hurdles to international genomic data use.

GIF solves problems. Organisations in the forum pilot GA4GH products in real-world situations. Along the way, they troubleshoot products, suggest updates, and flag additional needs.

GIF Projects are community-led initiatives that put GA4GH products into practice in real-world scenarios.

The GIF AMA programme produces events and resources to address implementation questions and challenges.

NIF finds challenges and opportunities in genomics at a global scale. National programmes meet to share best practices, avoid incompatabilities, and help translate genomics into benefits for human health.

Communities of Interest find challenges and opportunities in areas such as rare disease, cancer, and infectious disease. Participants pinpoint real-world problems that would benefit from broad data use.

The Technical Alignment Subcommittee (TASC) supports harmonisation, interoperability, and technical alignment across GA4GH products.

Find out what’s happening with up to the minute meeting schedules for the GA4GH community.

See all our products — always free and open-source. Do you work on cloud genomics, data discovery, user access, data security or regulatory policy and ethics? Need to represent genomic, phenotypic, or clinical data? We’ve got a solution for you.

All GA4GH standards, frameworks, and tools follow the Product Development and Approval Process before being officially adopted.

Learn how other organisations have implemented GA4GH products to solve real-world problems.

Help us transform the future of genomic data use! See how GA4GH can benefit you — whether you’re using our products, writing our standards, subscribing to a newsletter, or more.

Join our community! Explore opportunities to participate in or lead GA4GH activities.

Help create new global standards and frameworks for responsible genomic data use.

Align your organisation with the GA4GH mission and vision.

Want to advance both your career and responsible genomic data sharing at the same time? See our open leadership opportunities.

Join our international team and help us advance genomic data use for the benefit of human health.

Discover current opportunities to engage with GA4GH. Share feedback on our products, apply for volunteer leadership roles, and contribute your expertise to shape the future of genomic data sharing.

Solve real problems by aligning your organisation with the world’s genomics standards. We offer software dvelopers both customisable and out-of-the-box solutions to help you get started.

Learn more about upcoming GA4GH events. See reports and recordings from our past events.

Speak directly to the global genomics and health community while supporting GA4GH strategy.

Be the first to hear about the latest GA4GH products, upcoming meetings, new initiatives, and more.

Questions? We would love to hear from you.

Read news, stories, and insights from the forefront of genomic and clinical data use.

Attend an upcoming GA4GH event, or view meeting reports from past events.

See new projects, updates, and calls for support from the Work Streams.

Read academic papers coauthored by GA4GH contributors.

Listen to our podcast OmicsXchange, featuring discussions from leaders in the world of genomics, health, and data sharing.

Check out our videos, then subscribe to our YouTube channel for more content.

View the latest GA4GH updates, Genomics and Health News, Implementation Notes, GDPR Briefs, and more.

Discover all things GA4GH: explore our news, events, videos, podcasts, announcements, publications, and newsletters.

13 Oct 2023

Understanding how individuals view their genetic information — whether they see it as unique when compared with other medical information, and what consequences this might have on their views about how their DNA should be stored, accessed, and shared — will assist in informing future policy choices.

A person’s DNA can be uniquely identifying, it can also link the person to their relatives, and it can provide information about their past, current, and future health.1 Whether or not these features make genetic information somehow “special” when compared with other types of medical information is widely discussed and contested in ethical and legal discourse.2 Genetic exceptionalism refers to the idea that genetic information is uniquely powerful and uniquely personal, meriting unique protection.3 Concerns about privacy have driven much of the debate about this need for special treatment.4

Genetic exceptionalism is currently recognised in legislation in some countries, but not others.5 For example, the USA’s Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act 2008 regards genetic information as unique — warranting increased protection. In Australia, in contrast, an attempt to introduce similar legislation failed, and instead the legal requirements relating to the collection and use of genetic information are the same as for other medical information.6

It is important to understand how individuals view their genetic information — whether they see it as unique when compared with other medical information, and what consequences this might have on their views about how their DNA should be stored and shared, and who should be able to access it. This is especially important given that research to improve our understanding of the role of genetic factors in health and disease is dependent on the involvement of a large number of individuals from diverse populations. Understanding the factors that influence the decisions of individuals about whether or not to participate in genomic research will assist in informing future policy choices.

The Your DNA, Your Say (YDYS) study is the largest international study of attitudes towards the collection of genetic and medical data. It collected survey responses from 37,000 people across 22 countries. The survey asked a number of questions about the factors that might influence willingness to donate DNA and medical information, including whether DNA was viewed as being different from other types of medical information.

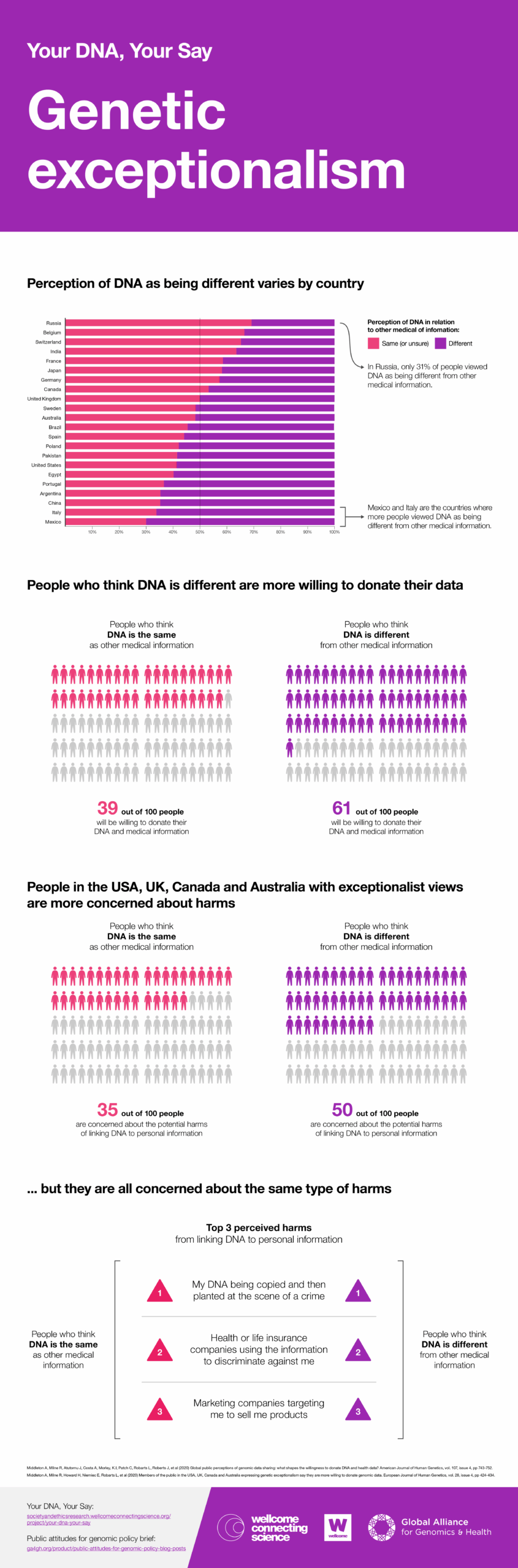

Overall, 53% of respondents across all 22 countries viewed genetic information as being different from other types of medical information, but the percentage of respondents sharing these views differed substantially between countries.7 For example, over 65% of respondents in Mexico and Italy viewed genetic information as being different from other forms of medical information, whereas only 31% of those in Russia did.7 The reasons for these differences in views between countries have not yet been fully explored, and warrant further analysis.

Views on genetic exceptionalism were not found to be correlated with decreased willingness to donate genetic or other medical information in any country. There was either no association or, in some instances, a positive association. Across the sample, participants who were unwilling or unsure about donating their medical and DNA information were less likely to express genetic exceptionalist views.8

A more detailed analysis was undertaken of the aggregated survey data relating to genetic exceptionalism in the UK, USA, Canada, and Australia. This analysis revealed that genetic exceptionalist respondents were substantially more likely to accept that their “anonymous” DNA and/or medical information should be donated for research purposes (65.3% of genetic exceptionalist respondents versus 47.1% of non-exceptionalist respondents). Genetic exceptionalist respondents were also more likely to be influenced in their decisions about whether or not to contribute their genetic information to research by the prospect of receiving a personal readout of their DNA (50.6% versus 30.2%) and by knowing there are legal protections in place to prevent exploitation (63.9% versus 47.2%).

This smaller analysis revealed further associations between genetic exceptionalism and other factors that might influence willingness to donate.9 As a starting point, respondents holding genetic exceptionalist views were substantially more likely to think that linking personally identifying information to their genetic information could potentially harm them in some way (49.5% of genetic exceptionalist respondents, compared to 35.2% of respondents who did not hold exceptionalist views).9 The three potential harms most commonly selected by respondents across the four countries were: “my DNA being copied and then planted at the scene of a crime”; “health or life insurance companies using the information to discriminate against me”; and “marketing companies targeting me to sell me products.” Analysis of a Costa Rican YDYS sample similarly emphasised the predominance of concerns about the use of genetic information by insurance companies or for employment discrimination.10

In summary, the aggregated survey data from the UK, USA, Canada, and Australia revealed that those respondents who held exceptionalist views were the most likely to be willing to donate their DNA and medical information to research, while also being the most likely to understand linking DNA to personal information could cause harm.9

We are only just starting to understand the ways in which genetic exceptionalist/non-exceptionalist views might affect perceptions of the potential harms arising from linking genetic information to other health information, and attitudes towards participation in genomic research. It is important to better understand these factors, given that over half of the respondents surveyed in YDYS expressed genetic exceptionalist views. In addition, although the YDYS survey revealed differences in the percentages of respondents expressing exceptionalist and non-exceptionalist views between countries, we do not yet have a good understanding of the reasons for these differences. For instance, we do not know whether the existence of genetic exceptionalist legislation might have any bearing on the views of respondents towards genetic exceptionalism. Nor do we have detailed analysis of the differences between countries in respondents’ views about the potential harms of linking genetic data with other health data. Clearly, more analysis is needed to better understand the views of the public in this regard.9

The YDYS study revealed that more than half of the respondents to the study had genetically exceptionalist views. However, this proportion varied substantially between countries. Because genetic exceptionalist respondents are more likely to donate their DNA and medical information than other respondents, it is particularly important to understand the local factors that might influence their willingness to participate. The fact that they are more concerned about potential harms than other respondents has policy relevance. For example, detailed analysis of aggregated data from the UK, USA, Canada, and Australia showed that misuse, discrimination, and direct marketing are all relevant concerns, illustrating the importance of developing robust infrastructure measures and appropriate legal protections to deter such activities.

This brief was written by Dianne Nicol, Richard Milne, Maili Raven-Adams, and the GA4GH Public Attitudes for Genomic Policy team within the Regulatory & Ethics Work Stream. The YDYS study was designed and led by Anna Middleton.

This brief is part of the Public Attitudes for Genomic Policy series of blog posts, developed by the GA4GH Regulatory & Ethics Work Stream (REWS). Read past briefs.